Crispian Sallis is an Oscar nominated Set Decorator recognised for his work on Aliens, Driving Miss Daisy and Gladiator and an Emmy winner for The Tudors. Other projects which jockey for position on a star studded resume include Oliver Stone’s JFK and Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys. For his latest film, Waiting For The Barbarians, Crispian recently took time out to talk production design and set decoration with Martin Carr. We discussed Crispian’s passions, his proclivities and why teamwork will never just be about a lot of people doing what he says.

How did you go about establishing a grounded reality through production design for this film?

To begin with I felt a duty to the book which was so beautifully written. It was clear that the author, Nobel Laureate J. M. Coetzee, employs language with great care and deceptive simplicity. He manages to hold the most complicated conversations and discuss philosophies and emotions within a finite framework of words. One of my tasks was to deliver that simplicity to the screen. This was my first consideration when it came to the magistrate’s town. To begin with, we had to conjure up a nameless dominion on the edge of an unidentified but realistic empire, enabling audiences to believe we were on the edge of a vast desert in the middle of nowhere in an unspecified era or time (though set, roughly, in the first half of the nineteenth century).

In terms of establishing a grounded reality what I chose to do, alongside costume designer, Carlo Poggioli, was to not over complicate things. That reality, for us, was based on this nameless place that the empire had all but forgotten. I wanted to create a fort that had strength and looked capable of dealing with stormy weather as well as repelling all borders, while from a design perspective I simplified all the architectural lines. In simplicity was strength.

In terms of the fort from an aesthetic perspective, was there any research you undertook prior to establishing any design choices?

I vaguely had in mind those old forts from movies of the Thirties and Forties with Douglas Fairbanks Jr., but my intrinsic research was to do with light. I became obsessed with how light would enter these sets. Collaborating, in part, with cinematographer, Chris Menges (Oscar winner for The Mission and The Killing Fields) who would take the process to fruition once the building works were done, my obsession extended to finishes and texture in terms of how light from windows, oil lamps and candles interacted independently with each set or location. As such, my research expanded to include nineteenth century oil paintings and examining sumptuous pictures taken by amazing photographers of all periods. My prime intention throughout was to glean information for the application of light thereby allowing the sets to bring additional depth to the characters and to the film.

In terms of character there is a distinct class of both ethics and demeanour. How did you make those distinctions between them through the production design?

Colonel Joll (Johnny Depp) arrives at the town with very few possessions and there was little opportunity to flesh that out beyond what was in the script. However, The Magistrate (Sir Mark Rylance), by contrast, is extremely layered and quite obsessive, especially with his archaeological findings. He is an historian and a gatherer who accumulates and studies artefacts as well as studying people. When Colonel Joll arrives, he is evidently disinterested in the Magistrate’s passions, so it was mainly down to Carlo, through costume, to influence their characters more than I. However, I like to think the town itself was a character in its own right.

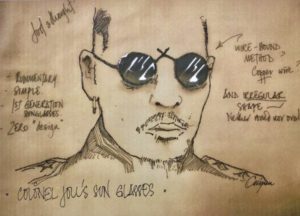

I did encourage the use of sun glasses in connection to Colonel Joll, which are mentioned prominently in the script as well as the book. Director Ciro Guerra approved my initial sketches for them and, again, I felt they should be rudimentary at best. These are first generation sun glasses which I felt should be fashioned from copper wire, as well as being neither too round nor too square. Cinematographer, Chris Menges, inputted the type of glass which formed the lenses. We ended up with three different versions, each made to accommodate his various lighting requirements. There is also a swagger stick and brass hammer, the former of which, I gave to Johnny on his first morning of shooting, which he loved. There’s also an old Marrakesh horse-drawn taxi carriage which we purchased and I had stripped back to the chassis and rebuilt to my design into the carriage of Colonel Joll’s you see on film. That was a fun project in itself.

For me the glasses and swagger stick are intrinsic to the character because they give Colonel Joll a certain rigidity, whilst also doubling as an additional barrier to the audience.

I think they both possess a certain refinement and there is no question that they helped Johnny portray the character with elegance. However, through that characterisation he cut Colonel Joll back to the absolute bone, making any additional theatrical flourishes, such as his glasses or the swagger stick, things to absolutely relish.

Thematically the film explores humanity’s desire for progress in the face of tradition. To what extent were these themes considered during the creative process?

I think the film comes down to perspective and ultimately that is what was fascinating for me. The Magistrate is clearly an intellectual, noble, kind and worthy. He has been running this town for many years and is clearly at one with its people. You get a sense, through his interactions, that he has had several relationships but it appears that these personal connections have never lasted very long with any one person. With regards to the Colonel and the Magistrate, it is striking how these two characters are so diametrically opposed. Rarely have there been two characters so opposed on screen. They make for fascinating protagonists, I think.

Despite his use of horrific, barbaric, medieval methods to uncover the “truth”, the question as to whether Colonel Joll’s opinions are any less valid compared to The Magistrate’s absolutely drives this film. Ultimately, the question is whether the Barbarians independently rose up in rebellion, or were they provoked by Colonel Joll? You also have to wonder what role the Girl may have played in provoking the uprising of her people as a result of her reporting what went on in the town. I like that angle too.

I think that has to be the number one aspect the film chooses to explore over the book, where the Barbarians do not make an appearance. In that respect, Waiting For The Barbarians is similar to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, being that Godot never appears either. I am lucky enough to say that Mr Coetzee became a good friend over the course of making the film but even now I’m not certain I know his view as to whether he wanted the screen version of his story to end with the Barbarian rising or whether that was a construct of producer Michael Fitzgerald’s and director Ciro Guerra’s vision.

That is the main thing to take away from the film: the debate on the differences between these two men, The Magistrate and Colonel Joll, in terms of their individual humanity and approach to human nature and authority. It seems that the town will revert back to the magistrate’s sense of normality once the soldiers have left, until that bugle sounds to announce the barbarians are coming. If I were to come down on one side in terms of character it would be to side with The Magistrate of course. The thought of Colonel Joll’s more inhuman approach is somewhat unappealing but it makes for a fascinating cinematic duel, don’t you think?

I must add, if I may, it was producer Michael Fitzgerald who acquired the rights to the book some twenty five years ago and originally tried to get the film made with the legendary John Box as his Production Designer. John had won Oscars for his work on Lawrence Of Arabia, Dr Zhivago, Oliver! and Nicholas and Alexandra. It was an honour that Michael invited me to tread in his shoes all these years later.

What do you find are the differences between working on larger tent-pole productions, such as Gladiator, and smaller productions having done both?

Of the large scale film makers I have had the pleasure to work with including Oliver Stone, James Cameron, Michael Cimino and the Scott brothers, each has their own personality. What you learn to do quickly is tailor yourself to their requirements. It all starts with the script. In terms of Waiting For The Barbarians I was sent the script and just saw the name J. M. Coetzee and read it and fell in love with it, to be honest. Subsequently the book became as much of a bible to me, opening itself up to relentless probing and informing all or many of my creative choices. These included such literary gems such as the fish mosaic in the desert which was not in the script. It was a nice touch, I thought, and a pleasure to include in the design.

In terms of tent pole and smaller films I think it is a pleasure of the job to work on both. In some cases, smaller films turn out to be just as rewarding. For instance, I loved designing Shane Meadow’s early films, A Room For Romeo Brass and Once Upon A Time In The Midlands. I love them all, large films and small, and working in television is a completely different challenge again to film productions of all descriptions.

What other factors do you think have an impact when it comes to production size?

I think timeframe is clearly part of it, as well of course as budget. On Gladiator, I remember flying back from Italy where one of the producers, Oscar-winning Branko Lustig, had accompanied me to Rancati, the great prop house in Rome. I had chosen my Roman artefacts and we were figuring out how much it would cost to rent them for the duration of filming. My budget for that film was huge but it wasn’t enough! I made the suggestion of getting most of my furniture and dressing made in India and he approved: it saved a fortune! I suspect Ridley would have liked six chariots with four horses each, but had to settle for four chariots with two horses each. It amazes me to think what James Cameron and Production Designer Peter Lamont, my old friend and mentor from Aliens and three Bond films, achieved on Titanic. The main ship set was many feet shorter than the original.

Do you think if they had had even more money would they have built the whole thing?

The fact is, they compromised, as did Ridley with his chariots, as I did with my set dressing on Gladiator, but did anyone notice? I doubt it. As with all walks of life, you learn to compromise sometimes, whilst hopefully staying true to your principles. Sometimes the compromises lead to even greater achievements than you first might have envisaged.

In the case of Waiting For The Barbarians the budget was minimal and I had twelve weeks prep which proved to be the most amazing challenge. I was daunted, but also hugely inspired by the prospect and by Michael’s passion and Ciro’s overall vision and Mr Coetzee’s book and script and just took on the challenge with both hands, and feet! Much of the furniture on this film I again sourced from India over a four day trip. I filled four forty foot containers which were then shipped to Morocco. It saved a fortune and all of it looked rather beautiful, I think.

Speaking of the set decoration, one of my first decisions shortly after joining the film, was to approach Michael Fitzgerald and suggest I become my own set decorator, which made perfect sense. He agreed. It saved a lot of time on my part having to explain a brief to someone else, effectively rolling the job of production designer and set decorator into one, and again, it saved a lot of money. Every film is different, whether it’s Waiting for the Barbarians or 12 Monkeys or Gladiator or Bond or JFK or Driving Miss Daisy and it always starts with the script. I loved every aspect of Waiting for the Barbarians, it was a total joy to work on from beginning to end.

If you could have given yourself one piece of advice when you started out what would it be?

The first job I had after leaving school was working for Michael Winner on The Big Sleep. Michael created more than his fair share of catchphrases, but at least one I hold very dear was, ‘Teamwork is a lot of people doing what I say!’. Hysterical! There is one word I look for without fail when interviewing people for jobs, which is “enthusiasm”. Michael looked for enthusiasm in me when he hired me. In a nutshell, I tend to hire people who express genuine enthusiasm in their interview. What I most want is to enjoy someone’s company and find that they are enthusiastic for what we’re doing. Talent is a useful addition but I always go for enthusiasm first and foremost. If they then manage to follow my instructions and do what I ask them to do, then we will get on well and the film will be delivered on budget, on time and look stunning. Seriously, I love everyone I work with making suggestions, that’s teamwork! It is part of the fun, taking on board other’s suggestions. Not something Michael Winner did particularly!

Describe for me your perfect Sunday afternoon.

My perfect Sunday afternoon would be spent happily watching a Grand Prix on Sky then going for a walk with either my children, my loved one or on my own. Taking in the countryside and enjoying being one with nature.

Perfect.

Many thanks to Crispian Sallis for taking the time for this interview.

Waiting For The Barbarians is streaming on Hulu from December 5th.